Plot hooks. Mysterious locations. Old maps.

A sandbox style game is not - as a physical sandbox - simply a blank slate on which players mold the world to their liking. Instead, there are adventure sites, factions, towns, landmarks, and wilderness for the party to experience and explore. The sand, so to speak, has been formed - it has an existing state - which the party can expect to discover at the table. Whether they re-form it or not will depend on how successful they are over the campaign - but in order to kick-start the adventure, in order to inspire the group to move out of the tavern and into the adventure, hints - incentives - have to drop.

One doesn't give the players a blank sheet, 3d6 down the line, and ask them where they are going: instead, they have to have leads - they have to have ideas which may guide them into the unknown.

And this article talks about one of my favorite aspects of doing just that.

An Unreliable Narrator

Acne during pregnancy does not indicate a female child - though that doesn't stop certain relatives from telling you as much. Consider - not all rumors are true; not all maps are accurate. If that is true in real life, why wouldn't it be true in your campaign world as well? Some of the things that your party hears - be it carousing at the tavern, be it scrawled on the wall of a shallow crypt - will be valid information: but some of it will not.

Key word some.

What you don't want to do is to destroy the trust, to instill an instinct of unbelief, in your players whenever they come across information. If the bartender is always evil - the party will never trust the bartender; if the map is always inaccurate, the party will leave it where they found it in the hidden library. As such - you want to have some of the rumors and hooks lead true - bring the party where the party expects them to go - while other rumors and hooks do not. Of the hooks that do not lead where they say they will, it's also important to ground them: some of them will be total hogwash - perhaps intentionally perpetuated by other adventurers to throw off rival parties from the trail of a find; perhaps seeded by malign NPCs (living or long passed) who were seeking a particular end - but some of them will be based on truth. Some of them will have a hint at what was found before, only to have been lost in a game of telephone, ear to ear and embellishment to embellishment as the tale is passed around varied campfires.

And it's up to you - the referee - to determine which is which so that the party can thereafter root out what's what.

One Third / One Third / One Third

When preparing rumors and hooks, I like to break out a table - typically 1d12 - to contain and randomize which ones the party finds or hears. These are divided into three, even in number, among the degree of their veracity:

-

True - True rumors are hooks which are correct. The map says it goes

through a cavern of scorpions and terminates in a well, at the bottom of

which is a magic sword - and the party, following the map, finds a cavern,

scorpions, and beyond that, a well containing a magic sword. Simple, easy,

for a ref.

-

Partially True - The partially true rumor is the tale inspired by a

seed of fact germinating into a sprig of maybe. Fishermen tell tales of a

cave visible at low tide where pirates and outlaws once stowed their gold -

but upon arrival, the party may find a cave: but instead of pirate gold, a

skeletal guard keeps watch over an ancient weapons cache from a fallen and

advanced civilization (a dead pirate near the entrance, perhaps, as they may

have not gotten as far as the fishermen thought).

These can be the most fun to come up with, as they will throw the party a curve ball: test their skill at the game both from a resource planning and execution perspective but also from an adaptation perspective: or they can be used to introduce other elements of campaign lore or lead to more adventure.

-

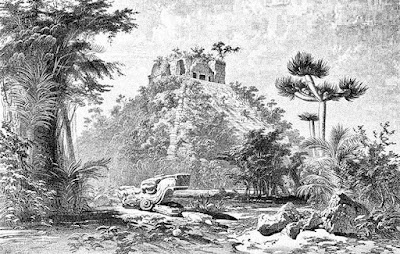

False - Lastly, a false rumor is one which has no basis on fact. The

drunken veteran claims you should expect a pyramid on the far side of the

vine-choked hills - but no pyramid looms. The sages say that a race of white

apes inhabits the low pass but can be appeased with spiced fruits: but their

tomes and records are old and the apes have been hunted to extinction by an

insect species whose tastes have developed a fondness for flesh. There is an

adventure to be had - surely - however it will not be the adventure that the

party expects!

Why a 1d12 table? For me - it's easy to roll on the table and provide quickly what the party encounters without allowing myself a bias. If it's up to the dice, it's not going to be influenced by how pressed I am for time this month and want to get the adventure moving; it's not going to be changed because I happened to watch The 13th Warrior this week and feel the need to plagiarize the Horns of Power twist. Similarly - when I remove a false rumor, I can replace it with another false one for next time; or when I remove a true rumor, I can replace it with another true. This will keep it varied and - by law of averages - prevent a pattern from developing. Over time, the group will encounter a mix, they will not mistrust the rumors (or trust them blindly) because of me - the delivering ref - and thus, the group will see more role play. They will spend time investigating - they will interact with more elements of the world to help them figure out the likelihood of whether it's true, false, or somewhere in between. And then, planning accordingly, they can set off with the best possible odds their skill can stack.

Can I have my players roll on the table? Absolutely. Players love

rolling dice. In so doing, however, it's important to change things up. You

don't want them to see a 3 and think, "Well, this hook is going to be a lie -

I keep carousing for another." Change up the numbers - maybe structure the

table a bit differently - or maybe have three tables and you, the ref,

determine which one is true/false/mixed in secret. It's good to have the

players roll - when the players roll, they tend to own the result a lot more

readily than if the result is "assigned" to them by the referee - however it's

also important to reject the pattern: don't allow them to figure out the

mechanism, the nature of the rumor, from the dice result: only give them the

information that they receive. It will be up to them to pry for more in

character.

What not to do: Regardless of rumor, regardless of hook - and I've been

saying "rumor", but this same principle can be applied to anything you tell

the players, any information that they find - regardless of the nature of the

rumor encountered, it should always lead to adventure. A false rumor

should never dump your players in a desert only to feel the fool for having

followed a lead that led them astray. The point of the game is the

adventure - and having lost one will leave a sour taste in the mouths of

everyone at the table - you, the ref, included. No one benefits from a bad

session. Thus - it's important to remember, all roads lead to adventure: it's

simply the expectations of the party that are up in the air. A false

rumor may take longer to reach, a false rumor may end up entangling the party

in a web they did not intend, or a false rumor may end up empty: providing

nothing more than a seed to another adventure - but whatever it does: it

should do so with style: it should do so with encounters, maps, problems, and

exploration. It should reinforce the experience the game is designed to

produce, even if it expressly doesn't provide what the players were

expecting.

And Them's My Two Coppers

Thank you for reading - and I hope it finds application to your game.

Delve on!

Public domain art retrieved from

OldBookIllustrations.com

and the

National Gallery of Art

and adapted for thematic use. Attribution in alt text.