TL;DR

For usability purposes, a summation of the beyond is provided here succinctly. For each door - roll three 8-sided dice, one for each column in the chart as follows, to randomly determine mechanical characteristics of the door, with something special happening on the extremes:

| d8 | State | Concealment | Protection |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Locked |

Hidden |

Trapped |

| 2 | Stuck | Not Concealed | Unprotected |

| 3-6 | Closed | ||

| 7 | Stuck | ||

| 8 | Ajar! | Secret | Trick! |

For a more detailed explanation of the above, read on!

Dungeon Doors on 3d8

Procedures exist in every edition of the game and every respectable clone or inspired system to assist in the placement of traps, treasure, and monsters - as well as intriguing room and map elements to both help in making dungeons come to life for the table and also to create in a randomized manner: allowing for unique and undreamed, unpremeditated adventures and ease of cognitive burden on the running referee. Among these tools are countless special room generators, special monster customization, and dressing tables to make the corridors and chambers breathe... but lacking among these tools - by comparative dearth to abundance - the exploration of the simple door.

Doors are essential to the dungeon experience - providing barriers, choke

points, intrigue, or entry and egress to and from dungeon rooms: but

surprisingly little thought goes into them. Some generators will color them

for you - tell you the make, model, and defining characteristics; some

generators will tell you how many to place or what's on the other side - but

generally, the system assumes that locks, traps, and so on will be at the

discretion of the referee: peripheral to the story being told by the

floor-plan rather than a driving factor herein.

So - in an effort to help contribute to that emergent dungeon building: to allow the doors to help explain the construction rather than to be tacked onto it - I wanted to share a mechanism to make doors interesting: dungeon doors on 3d8.

Procedure

For each door - placed or generated using other mapping mechanisms - roll 3d8: each to determine or inform a quality of the door, divided between the doors State, Concealment, and Protection.

State

The State of a door is a representation of how it will pose a challenge (or not) to the party based on its present nature. It's somewhat of an abstract term - but the meaning becomes clear, considering the options for results in the table:

-

Locked: The door is locked and must be opened - either by the wiles

of a Thief or with a key.

-

Stuck: The door - swollen with moisture, hindered by rust, or perhaps

possessed of an inanimate malevolence imbued by the mythic underworld,

seeking to expel the party as an immune system for the dungeon - does not

open easily and requires a Stuck Doors check to open.

-

Closed: The default state of a door, the door is simply closed.

Visibility is prevented and sound is muffled, but the party may pass through

at their leisure.

-

Ajar! The door has been left open (or at least partially so!)

Visibility or audibility are not hindered: surprise is mitigated for (and

by) potential inhabitants - and other implications might arise appropriate

to the door having been left swinging on its hinges.

For games like 0e - where all doors are presumed "Stuck" and must be forced - the author suggests exchanging the two: that the party might be treated a quarter of the time or so by cooperative portals.

Concealment

The Concealment of a door is how (or if) the door is hidden from detection by those outside the know. The most effective way to prevent entry is to provide no entrance, is it not?

-

A door Not Concealed will have no concealment whatsoever. A character

walking into the space should be informed "there is a door in the wall at X

point" as part of the exposition and mapping routine. These will represent

the majority of doors.

-

A Secret door is one which is hidden in plain sight. A book case

which turns when a candle is removed; a false wall which will push back when

a latch in the floor is pulled - these are Secret doors.

- Lastly, a Concealed door - one which is hidden, but hidden only. A door which is hidden behind a tapestry; a trapdoor hidden under a rug; a portal which has been obscured using illusion magic to seem like part of the wall - these are Concealed doors.

What is the difference between Secret and Concealed? In a pinch - a Secret door may require a roll or the expenditure of a locating resource to find: by comparison, a Concealed door generally would not: and is uncovered through clever player actions.

Couldn't a skillful player who knows where to look figure out a secret door through clever application of player skill? Perhaps - and if the party, having done their homework, knows exactly where to look, a proud referee may allow it. However, consider that this is a brainstorming tool - not a rules-as-law prescribed process; consider what's in the room, what it's being used for by the dungeon denizens (or what it was used for by its builders) - and let the difference between a Concealed door and a Secret one fuel your imagination: not limit it to simply answer "Does the Elf get the free roll when passing it by or not?"

Protection

The Protection of the door is a second layer of security added by the

dungeon architect or the denizens since having moved in and adapted the space

to their purposes. Protection serves as a mean to discourage or prevent

passage by those who are not in the know - or to confound the utility of the

portal to those same interlopers.

-

Trapped: a dangerous if not lethal trap has been placed on the door!

Either apply your personal favorite, or for inspiration, potentially follow

up on a

3d8 trap idea generator.

-

An Unprotected door is much like the door to your home or to a normal

room. It has no particular qualities about it to prevent ingress or egress -

instead serving the simple purpose of separating the space.

- Trick! A Trick door has something clever about it - a ruse or an arbitrary quality, intentional or perhaps incidental to its use, which makes the door stand out. When a Trick is encountered, roll a follow-up d8 on the State table - applying both: or being creative when a duplicate or contradictory roll arises.

Ideas for necessarily creative Tricks, based on rolled results, might

be as follow:

Not all combinations are provided with suggestions above - some, perhaps "locked & stuck" for example, simply speak for themselves - but more importantly: this is intended as a creative prompt, not a definitive list - something to spur your imagination, challenge your players, and reinforce the theme and tone of your dungeon. Alternatively, if nothing comes to mind - you're more than able to treat a Trick! result as a Trap - or simply apply all conditions to the same door at once.

Isn't Concealment a form of Protection - even by your definition as provided previously? Yes - but the rolls should be separate. This is intentional - not because of any arbitrary grouping of qualities, but to promote the possibility that multiple characteristics of a door may turn it into a more challenging (and thus more memorable) experience - one likewise more open to player ingenuity and exploit.

And stop being a pedant.

Let's Try It Out

5, 4, 2: Closed, Not Concealed, Unprotected.

Well, that's anti-climactic.

3, 2, 3: Closed, Not Concealed, Unprotected.

Again, anti-climactic. But that makes sense, I guess: as you're going to have

a lot more doors in the dungeon than anything else - potentially only eclipsed

by corridors - and as such, you would want to have a majority of them be

pretty bog-standard.

7, 7, 8 (5): Stuck, Not Concealed, Trick! (Closed)

I will admit, this is my fourth outcome - I had a third which I discarded, as it was yet again a normal door - but I am pleased with having rolled an 8 for protection: as I was worried I was going to have to cheat to see how it feels.

The door is Stuck, firstly, but also Closed. Consulting our examples above -

we have "opens partly" (restricting either some figures from using it or a

number of figures from using it at one time) and "force one way, open the

other." Keeping things fresh, say... this door is a Dutch door - with one atop

the other. The bottom side (because 5 is odd, why not) is stuck: but the top

side will open with normal effort. The party - in exploration - may simply

find an annoyance climbing over and through: but in the chance that - on the

other side of the door - they find some cave Ogres: they may find their

retreat somewhat hampered (or - who knows? - if they can surprise them, maybe

a vantage point for cover to make missile attacks!).

And Them's My Two Coppers

In short, the majority of doors will be quite mundane - mathematically, one in

eight will be trapped (compared to one in six rooms, if using the B/X rules,

which will contain a trap) and one in four doors will be concealed or secret -

keeping the party on their toes and keeping the mystique of the dungeon

fresh.

Delve on, readers!

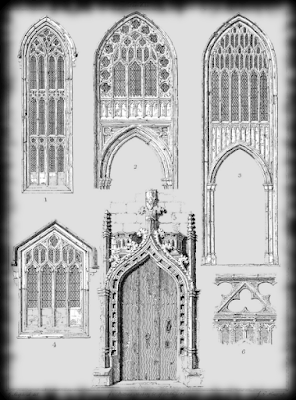

Public domain artwork retrieved from the

National Gallery of Art

and from

OldBookIllustrations.com

and adapted for theme and tone. Attribution in alt text.