Horrors wait in the shadows - asleep in the daylight, waiting for the red, wheezing star overhead to slip beneath the horizon or to blink out of existence entirely that they may wander forth, preying upon unwary travelers. Caravans brave the byways - dozens of armed men keeping the night at bay; lone travelers chance refuges and safe-houses, the owners or proprietors of which may be just as much the predators as the alien and chthonic creatures from which their guests are hiding.

And so it is - league upon league across a dying world - as societies and

civilizations forget one the existence of one another as history slowly begins

to foresee the passing of humanity into memory - Jack Vance's Dying Earth.

N-Spiration:

The Eyes of the Overworld and Cugel's Saga

About The Eyes of the Overworld

The Eyes of the Overworld was published in 1966 - officially - 16 years after its predecessor in Vance's far future world, The Dying Earth. I say "officially" published in 1966 as, like its predecessor, The Eyes of the Overworld was initially published in serial as a fix-up beginning in December of 1965, published, and then subsequently the second chapter, Cil - wherein Cugel, having achieved an initial acquisition of his objective, pursues its delivery through a kingdom cursed by a ghoulish creature preying on unprotected citizenry - was published standing alone in 1969 within an unrelated collection. It would later go on to be re-titled, Cugel the Clever, in reprint in 2005 - however, I mention these disparate mechanisms to support a commentary to its style: each story is interconnected, much more so than those in The Dying Earth before it, however each still stands alone - with more or less context - as a self-contained story, representing a stage of the journey Cugel is under: with one or two primary themes tying them together - namely, Cugel's curse to quest for and unrelenting desire for revenge upon the Laughing Magician.

But I get ahead of myself.

The Eyes of the Overworld introduces Cugel - our aforementioned

protagonist - as a wily anti-hero: a self-serving and self-aggrandizing

character, one who both survives by his keen wit and quick thinking but also

who provides his own downfall through a certain hubris. The author - in

addition to presenting the world tilted in the perspective of the Cugel

character despite still dictating in the third person - uses Cugel as an

instrument of drama and humor: mixing the thrill of adventure, the curiosity

of exposition and mystery, with comedic moments - situational or jibes from

other characters - with a dark undertone of variable intensity. His

juxtaposition against other characters - gullible or guileful characters,

noble or ignoble, each presenting an opportunity to have or be had - is used

to paint a cynical world: one that provides a stark commentary about the

nature of societal interactions - the relationship between the commoner and

the vagabond; the worker and the employer. In particular - spoiler contained

within the following collapsible tag - during Cugel's interactions with the

sorcerer, Pharesm:

Cugel, between the mountains and the forest, halfway in his journey home...

...to return the purloined Eye of the Overworld spectacle to the Laughing Magician Iucounu, comes across a perplexing series of stone monoliths arranged in an intentional pattern. He comes to learn this was the work of teams employed by a sorcerer - the lead of the workman team singing the praises of the employer, Pharesm. Pharesm, meeting Cugel, rejects him as an employee due to lack of experience and offers no hospitality whatsoever: which the workman lead also praises, displaying an almost toadying devotion and zealousness for the work to be performed. Thus - both of them are content to see Cugel (admittedly a stranger) go hungry off into the wastes - both of them are then disappointed when Cugel, alleviating the hunger they chose to ignore, devours the very being that the monoliths and centuries of research were designed to lure to Pharesm's study!

Pharesm goes on to attempt to conscript Cugel to recover the creature out of the past - which is thwarted by Cugel's own lecherousness and ignorance - but the message remains: if basic humanity, basic hospitality and understanding, had prevailed instead of raw self-interest (on the part of both parties), everyone would have been off for the better.

Like his other works within Tales of the Dying Earth, the chapters of each story are long: though some of them do have break points for those with bookmarks looking for an opportunity to rest their eyes. This is - also like most of the other work in the collection - due to the serialized publication strategy. Because each of them was, itself, a self-contained novelette, each of them would be of sufficient length to accommodate the trappings of a story arc and to draw value for the attention of a magazine or collection reader. However - due to the occasional breaks and due to Vance's evocative diction over imaginative vistas; our own world presented alien in the far future where the sun ages into decrepitude; and the intermix of humor as integral to the experience - I, myself, did not find the length to be bothersome. Each chapter logically leads into the next - and each satisfied enough to keep me turning the pages.

About Cugel's Saga

Cugel's Saga picks up where The Eyes of the Overworld left off: its first sentence, the first moment following the final events in The Eyes of the Overworld immediately. Published in 1983 - 17 years after its predecessor - it bears many of the same themes and tone, but is its own work: being significantly longer and written singularly (according to the author) rather than serially. Marketed as a novel, it still has a sense of episodic progression - and each of the chapters can be read independently - however the continuity between them is stronger and the context they provide next to each other is greater, contributing more heavily to the sense of events within the work as interpreted by the reader.

The premise of this work is a duplicate of the previous: Cugel sees himself the victim and seeks to return in order to have revenge on Iucounu, whom he sees as responsible for his current plight. Additionally, the process for accomplishing this end is the same as the prior - the presentation is that of a travelogue, each chapter (or section, depending on what you consider a "chapter") being titled according to the geographic: for example, his journey between the mud flats of Tustvold to the port city of Perdusz is contained in "From Tustvold to Port Perdusz." However - unique to this volume is the happenstances along the way - though the beginning and the destination remain consistent, the places, people, and story elements along the way are entirely new and their own: presenting an entirely new story within the context of the old.On the subject of theme, Cugel's Saga embraces the same direction but displays a renewed intensity. In The Eyes of the Overworld, where cheating or larceny is common, Cugel's Saga contains blatant murder. True - The Eyes of the Overworld is rife with examples of active malice (and does contain characters killing one another) it seems amplified in Cugel's Saga - example in his aforementioned journey between Tustvold and Port Perdusz:

Coming across ominous warnings against a wizard, Faucelme...

...Cugel encounters a group of farmers whose wheel is off the wagon. In exchange - perhaps - for safety over night (recall, the world is full of man-eating horrors in the dark) he uses a magical item to help them get the wagon moving: holding it partly aloft against the force of gravity. Instead, they muscle him out of his money - the cost of the wheel, they say, because they lost it while he was about - and set him on his way.

Continuing - Cugel takes shelter in the manse of Faucelme - who seems an absolute gentleman. Cugel ties him up, mistakenly using a magical rope over which Faucelme has total control and can escape at will, but instead of hostility, Faucelme offers Cugel entertainment, sup, and shelter... until he sees an artifact which Cugel carries. After which, Cugel not being willing to part with it Faucelme attempts murder by four separate mechanisms: poison at dinner and three separate trapped bedrooms: one of unknown hazard - but bearing no windows; a crushing mechanism on an iron framed bed; and finally a mysterious burst of presumably fatal gas in an otherwise nondescript room - all to obtain the artifact: a shining scale called Spatterlight.

Which is better, perhaps, than what could have happened - as the draft animals (intelligent enough to speak) for the farmers prior reveal that the farmers in bullying for cash did better than they did to previous travelers - whom they would offer shelter only to murder in their sleep: a habit which they stopped only because of the bother to bury the evidence!

These animals, Faucelme describes as drunkards - so they are not without their own vices - but truly: they are the least odious of the whole bunch!

Further, the theme of workman versus employer continues in Cugel's Saga - with Cugel having to out-scheme both a purveyor of antiquities who, through deceptive advertising, entraps workers with debt to the company (something that did happen in industrial America through the industrial revolution - and arguably happens to this day in the form of various avenues of credit... though that's another conversation peripheral to the review) to dig through cold mud pits, and then a second time - a merchant - who seeks to maroon Cugel and replace him: despite Cugel having uncharacteristically actually performed his role aboard ship faithfully.

Faithfulness and trust are rewarded with abuse and betrayal - throughout - and the crafty regularly come out on top: including both Cugel in moments of clarity and those around Cugel in moments where his own ignorance or naivety bites him. To my own reading - the ever-presence of this theme, the never ending predictability of every character to do the absolute worst thing possible in the service of their own goals came off as monotone: Vance's use of egocentric, Machiavellian characters draws a parallel to the more modern G. R. R. Martin's use of character morbidity: where, in the earlier works, the theme and tone serve an end and stand in juxtaposition to how the bulk of literature tends to turn - in later works, it grows sour: the inversion of the trope becomes the trope itself: becomes a gimmick - and the reader (or, this reader) grows weary of the pony performing its one trick. While I am not disappointed to have read Cugel's Saga, I will say that by the end of it, I was excited to have made it to Rhialto the Marvellous.

But that said - mood lightening commentary in spoiler below:

Cugel, in his maritime adventures...

...takes on the role of "worminger." He takes it on not knowing a thing about it, lying a bit saying he simply has been out of the game for a while and would need to knock the rust off.

In a curious parallel - the author, Vance, was disqualified from military service during World War II because of his poor eyesight: not wanting to leave the sea, Vance would then go on to obtain and memorize an optometrist's exam chart - reading the lines from memory rather than sight - in order to join the Merchant Marine! He would go on to a successful career on the water until establishing himself as a full-time writer 30 years later - again, in parallel to Cugel, who learns the worminger trade (tending and goading a giant sea worm strapped to the boat and providing a mean of propulsion) and excels at it, better than the paired junior worminger who had served previously.

It's interesting to note - by the 1980s when Cugel's Saga was written, Vance was still an avid sailor, having left the Merchant Marine, but having lived on a house boat (with Frank Herbert and family - actually - SUCH AN INTERESTING LIFE VANCE LED) and having bought, rigged and operated multiple personal watercraft up to 45 feet in length - and that so much of Cugel's Saga takes place on the open ocean.

Habits and loves of the author injecting themselves into the work.

What's to Like?

Cugel is the archetypal thief.

Whether he is hiding in the shadows, striking from behind, or experimenting with (and making errors in) casting spells from written material - Cugel is, at least from the 1966 tome, quite an obvious influence on Greyhawk's Thief class. In that sense, there is value in this book for both player and referee in the portrayal and running of Thief-esque characters.

First, Cugel - he is not a fighter. He can fight, but he recognizes his own limitations (or seeks to avoid discomfort, at a minimum) in relation to creatures of the wild or to skilled or numerous adversaries. As such - the wilds being a dangerous place - Cugel finds himself constantly thinking outside the box to address situations he's in: negotiating with (or taking advantage of) other characters he meets, taking on roles or proverbial side-quests to gain access to what he needs for the next phase of his journey, or pitting others against one another in order to achieve his ends. The most memorable of these (to me, at least) being,

when approaching the Mountains of Magnatz...

...Cugel is followed by a deodand. Knowing he does not stand a chance in open combat, Cugel hides and attacks with a stone from above - a back-stab, so to speak: albeit with a bludgeon - wherein he cripples the creature. The deodand then goes on to bargain for its life - offering to guide Cugel across the mountains safely if he does not slay it.

Of course, being an evil thing, it goes on to lead him to three of its

fellows - who in turn are fortunately killed by rangers Cugel encounters:

who, in a technicality, as Cugel said he would not kill the crippled

deodand, Cugel encourages to kill the crippled deodand, its purpose and use

fulfilled - but this is a perfect example of doing business with a Chaotic

creature - one which players and referees alike can draw inspiration out

of.

Cugel's propensity for betrayal makes sense as to why a party might be wary of

a Thief - or why Thieves as specialists often cannot be employed by a Lawful

party for long.

Lastly, consider the spell Geas. In the original edition of the game - wandering magic users, Wizards in particular, were a hazardous encounter, as where a name-level Fighting Man will demand a joust or a name-level Cleric will demand a tithe, a Wizard will demand a quest, a favor, and will do so at the threat of a slowly worsening curse until such time as the geas is fulfilled.

...in The Eyes of the Overworld and Cugel's Saga both, this theme is iterated: at least twice, magic users take advantage of the common man (and of Cugel, specifically) leveraging compulsive magic:

- Iucouno, compelling Cugel to seek the eyes on pain of being tormented by Firx, an alien barb attached to his liver.

-

Pharesm, sending Cugel into the past with an amulet which will only return

him to the present when its purpose is fulfilled.

As a plot device, it's convenient - arguably lazy - but as an OSR trope?

Priceless.

What's to Toss?

In reviewing the magician-themed Dying Earth tales, I warned the reader that the oldest of the stories were written over 80 years ago and as such, language and themes would not match up to what you might expect from fantasy fiction written today. While this holds true for The Eyes of the Overworld and Cugel's Saga - the newest of which was published around the time my median reader was born - what stands out more so in the Cugel stories is the severity and darkness of their themes. While bandits and a nihilism brought on by pending heat-death in darkness is surely grim in both cases, in the Cugel stories, it becomes ubiquitous - there is no good in humanity: under the fading red sun, kindness is repaid exclusively with predation.

Further - consider the following; spoilered in collapsible panel, as with the other in-text examples:

In this sequence, Cugel is subjected to a prank by several barnacle elves, as I was considering them. They are sedentary sea life - fey, by the seeming of it, and their mastery of the strange liquid gossamer referenced. In response to being wet - imagine having a child throw a water balloon at you from a tree fort - Cugel reacts by pulling the creature out of its shell and spilling its entrails on the beach.A hyperbolic overreaction intentionally, sure, for humor's sake - and the reaction and commentary thereafter is used for humorous effect - but Cugel is totally remorseless and indeed self-justifies the act, moving on as though nothing had happened, incident remembered only to try to short-circuit the barnacle child's dying curse laid upon him, once his jerkin dries out.

Arguably, this is not a human. It is a fictional creature whose species is never heard of again in Vance's writings. Similarly, this is a work of total fiction: am I not over-reacting to this?

Perhaps. But then, further along in the very next chapter:

Having escaped the well-incurred wrath of a demon-mastering heir to the kingdom of Cil, Cugel and a companion continue in trekking back towards Almery, where the magician Iucounu resides. Encountering a group of ruffians who inform the travelers that a glade they seek to cross is in truth haunted by fey and that they would need guidance across. In exchange - they demand payment: the involuntary servitude of Cugel's newly acquired female companion, Derwe.

Cugel convinces her to to trust him - that he has a plan.

Along the way, they bind her in shackles, they move through the forest outnumbering him, and in the end, you're unsure of whether or not he needed them at all - but through the whole ordeal, the reader is considering, "What is this plan? How will Cugel get through this one?"

And then... he sells her.

That was the plan all along.

In reading this - I actually (and I expect many others would have) experienced a rising suspicion, an enjoyment in realization, as the tension built. The reader may see what's happening, may understand what the endpoint is going to be - and for me, at least, I drew great pleasure from the build-up and reveal: chuckling audibly to myself when it finally happened. However, that said, the fundamental joke here is human trafficking: a very real and very serious thing that persists into the modern day.

Then, in the Mountains of Magnatz...

...after having been fooled into taking to a watch tower from which there is no returning, Cugel escapes and kidnaps a woman, Marlinka of Vull - to whom he had been ceremonially wed as part of the fooling, an inducement to take the role of watchman.

In his own words, Cugel is simply taking what is his due: behaving in the

manner expected of himself. However, in reading this chapter, I had to read

this twice - the first time through, having thought "Is this a fade-to-black

rape?"

On the second reading - no - no it was not: and I hesitated to post this

comment in the review as the subject material is serious: it does not bear

diminishing. But be advised, potential reader, this kind of language occurs

at least once, as referenced above - and is something to have in the back of

the mind.

Again - in context - these are fictional people, fictional characters,

introduced to tell an amusing story: and knowing that is the grain of salt to

take when reading - but the presence of truly dark themes embedded sometimes

as humor and other times in earnest is at times - or, was for me at times -

intense.

On a more editorial note - regarding Cugel's Saga: reading Cugel's Saga can feel like I'm watching Airplane 2. Old jokes get repeated in new contexts, the same plot - and conclusion - gets rehashed. While Cugel's Saga does have great merit to it - in the story-telling, in the world-building, in the humor - by the end of the book, I had grown bored and at a few points, recall having had to force my way through it.

The Eyes of the Overworld is stronger than Cugel's Saga - and

The Dying Earth and Rhialto the Marvellous, to my reading, are

stronger as well. The Dying Earth in particular is the strongest of the

four: for its mystery, for its novelty, and for the manner in which it

explodes the world around you: the reader isn't drawn in - instead, the world

is forced out: a V.R. set without the goggles projected directly and suddenly

into your mind.

Further Reading

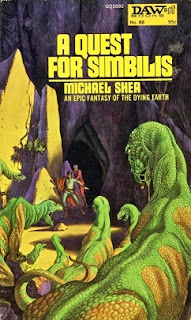

In my previous post regarding The Dying Earth and Rhialto the Marvellous, I mentioned the prolific nature of the Jack Vance library. This remains true - though I add little to the conversation by restating it. Instead, for those interested in Cugel directly, I have come across another book - A Quest for Simbilis - written by Michael Shea.

Shea - author of the series Nifft the Lean and multiple-winner of the World Fantasy Award for his own works as well as for his contributions to the mythos of both Vance and Lovecraft - wrote the piece, interestingly enough, in 1974 with the blessing of Vance, himself, with whom Shea was friends. It is a sequel to The Eyes of the Overworld, picking up Cugel's adventure where Eyes of the Overworld leaves off and following through on a quest for vengeance in much the same plot driver as Cugel's Saga but following a totally different narrative: presenting different stories, different adventures, and different outcomes for our antiheroic protagonist.

While I have not read A Quest for Simbilis, it is curious to note that

- having been written in between 1966's The Eyes of the Overworld and

1983's Cugel's Saga, it stood alone as the official course of events

for 9 years before Vance, the original author, orphaned it with his own

rendition of post-Eyes events. This in and of itself makes me curious

to see what's in it, on top of other reviewers agreeing: if you like the Cugel

stories, you may like Simbilis. So - if you're willing to roll the dice

on future reading, the dice for A Quest for Simbilis might be loaded:

and Michael Shea may find his way in months to come into the Clerics Wear

Ringmail N-Spiration series.

Conclusion

As with the other books contained within my purchased anthology, Tales of the Dying Earth, Vance's works are specifically called out in the 1e DMG's Appendix N - and as such, are by default seminal to the ongoing development of the D&D game at TSR and foundational to a fledgling referee's engineering of a tonally faithful campaign. The Eyes of the Overworld, having preceded even the original edition, would have been in Gary and Dave's minds - and I have no doubts that when Cugel's Saga came out years later, they would have binge-read on it, as well.

For that reason, The Eyes of the Overworld and Cugel's Saga has to be a 1: Very OSR.

Cugel is our prototypical Thief - and Cugel's story - or stories - is and are

emblematic of the prototypical OSR campaign. While there are some rough edges

and some moments where the seriousness and the silliness intermingle, do those

qualifications not also apply to most home games?

The Eyes of the Overworld and Cugel's Saga both make for a fine

addition to your Appendix N library and a fine inspiration for the games a

budding referee is yet to run.

Thank you for reading - delve on!

Tales of the Dying Earth, The Eyes of the Overworld, and Cugel's Saga are copyrighted Jack Vance and to the affiliated publishers of their respective distributions. First edition The Eyes of the Overworld cover art is by Jack Gaughan; first edition Cugel's Saga cover art is by Kevin Eugene Johnson. A Quest for Simbilis is copyright Michael Shea and DAW Books; the first edition cover art therefor being accredited to George Barr. Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, Dungeons & Dragons, and D&D and all imagery thereto related are property of Wizards of the Coast.

Clerics Wear Ringmail makes no claim of ownership of any sort to any of the aforementioned media, texts, or images and includes references to them for review purposes under Fair Use: US Code Title 17, Chapter 107.

The slide-in of Gary... I got from a meme.