Because they are keyed.

Drawing or finding a map is easy. Keying a map, stocking the map, takes time and not everyone - especially folks with odd or demanding work schedules or *cough cough* young children *cough* have time to devote to it. More so, random generators rarely provide the ever-interesting "Special" result: so keyed maps and modular adventures, wherever you find them, are idea mines. Don't like a map? Doesn't fit your setting? Grab the good stuff and mold it into your game!

Keyed maps and modular adventures are, at their best, plug-and-play sessions and at their worst, idea mines. Knowing that, and knowing that a core competency of mine lies somewhere in that territory, I wanted to elaborate on the method: how I operate. It's not an end-all be-all guide to how to make a map adventure: it's just the procedure I follow when I make dungeons and dungeon levels.

Concept and Theme

First and foremost, you'll want to come up with a concept for the dungeon. What are you trying to accomplish with this dungeon? How will this dungeon fit into a game world? Keep in mind - "I want a dungeon that is a hole in the ground with random critters guarding gold" is a perfectly acceptable and I would argue, to be encouraged, goal! A generic dungeon - especially a small one - can be a welcome diversion from ever-unique and infinite depths. While having too much generic or repetitious elements indeed can make the game more stale, losing the interest of the players, having some or just enough of the classical will encourage player skill - which I will elaborate a bit more about in a bit. Rangers don't get good at ranging without having ranges to range - so to speak: if your player latches on to the hunting of Hobgoblins: let them! It's known as emergent storytelling - if that character survives, it's now the protagonist of a Hobgoblin-hunting memory that you and the player group have created together.To that end - you may elect to highlight a particular theme: and this is a nebulous term. You can define it to be based on the dungeon's purpose - was this dungeon a library? a prison? - or you can define it based on the dungeon's intended occupancy - is this a lair for goblins? Is this dungeon a fungal cavern that is harvested by various local factions for magic mushrooms? Themes are particularly useful if designing lairs or locations of interest - while not mandatory, they can help guide your imagination during the stocking process.

What is the purpose of the concept, the theme?

The reason you want a concept or theme up front - and the reason it's important that it's up front - is because it will influence how you key and how you map the dungeon. If you go in with a concept in mind, it will be much easier for you to flesh out the encounters, the factions, and the map in a way that engages the players: rather than producing a random series of irregularly shaped boxes containing assortments of treasure and its guardians. Again - randomization is not a bad thing, nor are dungeons with a plethora of creatures: but if that's what you're going for - you want to commit to it: set that as your theme, your goal, as a guard against violating your theme.

The reason you want a concept or theme up front - and the reason it's important that it's up front - is because it will influence how you key and how you map the dungeon. If you go in with a concept in mind, it will be much easier for you to flesh out the encounters, the factions, and the map in a way that engages the players: rather than producing a random series of irregularly shaped boxes containing assortments of treasure and its guardians. Again - randomization is not a bad thing, nor are dungeons with a plethora of creatures: but if that's what you're going for - you want to commit to it: set that as your theme, your goal, as a guard against violating your theme.

Can a dungeon have multiple themes? Yes. That's where factions come from - the area occupied by the cultists should be different than the area that's unclaimed or that is occupied by the Kobolds. In that case, think of that subsection of the dungeon as it's own dungeon "level" - running through the process of dungeon creation independently for the themed area (primarily, the encounter list and stocking process: mapping, I tend to draw the map holistically first, and amend if needed). The lair element - the area occupied by a particular faction - should fit that faction: and treating it as such will produce a section of dungeon distinct from the rest that fits with how it should be, assuming that there are members of that faction making their home there: the cultists are less likely to have traps on every doorway, for example; or the Kobolds are perhaps less likely to have wandering acolytes on patrol.

Encounter Lists

Wandering Monster List

Based on the level of the map and the design goals of its contents, come up with a wandering monster list. In B/X, a d20 table is presented with different monsters whose number of hit dice match the level of the dungeon - 1 HD monsters on level 1, 2 HD monsters on level 2, and so on. You're absolutely welcome to use the tables out of B/X - or a third party table from a blog or other resource. If you make one yourself, don't feel compelled to have 20 monsters: you can have just six, or you can have 100 - if you want: keep in mind, however, that a wandering monster appears roughly every 12 turns - 1-in-6 chance every other turn - the broader your encounter list is, the less likely your party is to encounter one specific entry on it.Consider, also, your theme. If you are using a particular type of dungeon, try to craft or select a wandering monster table that reinforces the theme: for example, if you are building a set of catacombs beneath a forgotten mausoleum, rodents or scavengers would be appropriate on upper levels while undead would be more appropriate on lower levels. By reinforcing the theme, the players begin to predict what to expect and will plan accordingly - it does not constitute a failure of the DM for players to prepare properly: one pillar of the game being player skill, if players on a return trip to a dungeon come equipped with spells and items that are more effective against the themed list, that means you've successfully rewarded and encouraged a core tenant of old-school play. If they get the equipment/spell list right on the first try based on the rumors they hear about wherever they are going? You've double succeeded - as the player skill has increased and you've provided a consistent world. That's not to say you can't or shouldn't surprise your characters - but unless you're going for a total fun-house adventure (in which case, disregard this paragraph), surprises should be just that: a surprise. If every room is different, without verisimilitudinous transition, the dungeon will lack cohesion and the game will trend against serious play.

Consider factions - or potential faction play. Don't plan to have every encounter resolve via combat. Instead, think to include elements that may parlay, team up with, or betray the party: combat, apart from being a hazard and a resource drain, hardly makes a memory the same as a non-combat element that the player's made their way out of using their wits and elan.

Consider, last, your mechanism of resolution: Rolling a single die - 1d6, 1d20, 1d%, etc. - offers a flat distribution of probability: that is, each wandering monster on the table is equally likely to come up when you roll for an encounter. If you want preferential treatment - for one or a set of monsters to wander more than others - there are a couple options to solve the problem: first, the most common solution, is wide-ranges on a D% - so, if I am in a Goblin lair and Goblins, Wargs, and Hobgoblins are on the list, logically, I may give "goblins" 20% (results 1-20), "wargs" or "hobgoblins" 15% (results 21-35 and 36-50, respectively), and then divvy up the remaining 50% among other dungeon occupants.

Another option is to use multiple dice - so, 2d6, 3d4, etc. - and put more common elements in the middle. I personally enjoy the multiple-dice approach, as D% seems sterile to me, but be very mindful of the probability curve:

if your table is bigger than 2d8, or if your table has more than 2 dice - be mindful that the enemies at either extreme will become incredibly unlikely - with our goblin example, on 2d6, the easiest approximation for a 20% chance for "goblins" would be to key that encounter to both 5 and 9 - which have an 11% chance each. This will preserve your probability from above, but it will reduce the variety in the table: there are 11 possible results on 2d6 - so putting "goblins" onto two of them means a maximum of 9 other monsters will have assignable numbers. Similarly - consider your edges: rolling a 2 on 2d6 is the equivalent of applying just shy of a 3% chance. Increasing the die size to 2d8, the probability of a 2 drops to just shy of 2% - increasing the number of dice to 3d6, a 2 becomes impossible: but the probability of rolling a 3 is right about 0.5%: one half of one percent of rolls. Knowing that - your edge results, with this method, will become rapidly less likely to appear: at an average rate of one encounter every 12 turns, the party will have to be in the dungeon a long time and will encounter a lot of other wandering monsters before these special ones come up. Counter point - the dice love to defy probability: stories of several natural 20s in a row or encountering the 1-in-100 enemy right at the gate of the base town make for most memorable sessions - but regardless of those forum stories and copy-pastas: as personal advice, I would stick to smaller dice and smaller numbers of dice if using this approach.

if your table is bigger than 2d8, or if your table has more than 2 dice - be mindful that the enemies at either extreme will become incredibly unlikely - with our goblin example, on 2d6, the easiest approximation for a 20% chance for "goblins" would be to key that encounter to both 5 and 9 - which have an 11% chance each. This will preserve your probability from above, but it will reduce the variety in the table: there are 11 possible results on 2d6 - so putting "goblins" onto two of them means a maximum of 9 other monsters will have assignable numbers. Similarly - consider your edges: rolling a 2 on 2d6 is the equivalent of applying just shy of a 3% chance. Increasing the die size to 2d8, the probability of a 2 drops to just shy of 2% - increasing the number of dice to 3d6, a 2 becomes impossible: but the probability of rolling a 3 is right about 0.5%: one half of one percent of rolls. Knowing that - your edge results, with this method, will become rapidly less likely to appear: at an average rate of one encounter every 12 turns, the party will have to be in the dungeon a long time and will encounter a lot of other wandering monsters before these special ones come up. Counter point - the dice love to defy probability: stories of several natural 20s in a row or encountering the 1-in-100 enemy right at the gate of the base town make for most memorable sessions - but regardless of those forum stories and copy-pastas: as personal advice, I would stick to smaller dice and smaller numbers of dice if using this approach.In recent vintage, I've become enamored of the DX/X approach: that is, D6/6, D8/6, D4/4, etc. - rolling two dice and consulting a nested table. This is - in effect - very similar to the D% approach (which can really be considered D0/0, after all - as my d10s, at least, have a 0 on the tenth face)

in that you are rolling two dice - one for the "tens" column and one from the "ones" column - however in reviewing the wilderness encounter tables in the X side of B/X, one finds a prototype version of this sort of table-nesting: for example, rolling a 1 results in "Men" - or a 2, "Flyer. "Men" and "Flyer" both have their own follow-up table - complete with brigands, bandits, etc. and gargoyles, griffins, etc. respectively.

in that you are rolling two dice - one for the "tens" column and one from the "ones" column - however in reviewing the wilderness encounter tables in the X side of B/X, one finds a prototype version of this sort of table-nesting: for example, rolling a 1 results in "Men" - or a 2, "Flyer. "Men" and "Flyer" both have their own follow-up table - complete with brigands, bandits, etc. and gargoyles, griffins, etc. respectively.Effectively - Expert, producing wilderness encounters, rolls a D8/12.

Why DX/X and not table references? I like rolling several dice once - not rolling one, looking up the result, and rolling again: so it's quicker for me in play and prep to have a DX/X. Second, presentation for reference - the aforementioned "Men" table is fine, as the wilderness encounter first-table and the appropriate reference table are on the same page - X57 - but "Flyer" on the other hand is a page later on X58. Depending on your printout, flipping back and forth might not be a bad thing - but looking at a table as such on a PDF is problematic - as it's much more of a chore to flip back and forth in a PDF or on a web page than it is to simply leave a physical book or pamphlet open on the desk while you work. DX/X tables are less object-oriented than table references: but they are more usable - especially in an online format.

Stocking Encounter List

Optionally - after having come up with a wandering monster list - you may come up with a special encounter list, or a stocking monster list. This is the list - in my case - that I'll roll on to determine what's in given rooms. It may be a super-set of your wandering monster list - or it may be something totally independent - but in general, it should contain things that would naturally be in the rooms of your dungeon, based on your theme, factions, and other pertinent influences.| How is this different than a wandering monster list? Your wandering monster list will be rolled in play - as such, it represents moving elements. Patrols, commuters, scavengers... these are your wandering monsters. Although it is totally acceptable to populate a dungeon using the wandering monster tables - those wanderers have to bunk somewhere - the purpose of the stocking table is to house, in addition to mobile elements, less mobile elements: thematically appropriate encounters that will not be encountered unless the party discovers them in their nest. |

Doesn't Basic tell you that special monsters should be placed intentionally, along with special treasure, and the REMAINING space can be stocked procedurally? Yes. And if you want to do that - do that: in which case, this optional stocking encounter list, I don't create. The reason I include it, and the reason I use it when making dungeons that I don't have a particular layout in mind for, it can be fun to use a randomizer to determine where special or thematic elements reside - where the head cultist is, where the field of fungus monsters are (fungus doesn't walk around, now does it?), where the night-hags have set to roost. Doing so creates dynamics that don't arise when placing them manually: if two different factions are uncomfortably close to each other, the question then rises "why are they so close?" and "how does this proximity influence their behaviors?" Additionally, it leaves room for surprises - mentioned above. It is then an avenue to guard against accidentally formulaic layout choices and insurance that surprises remain an exception to the norm, preserving their designed capacity to keep the party on their toes. |

The Map

Drawing the Map

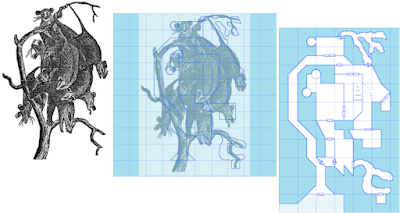

There are dozens of posts on how to generate a dungeon - there are articles and sections in rule books as well - and there are also random generators, some linked in the introduction of this post that are based on those articles and sections. They are great resources - and I would be tempted to use them.That said, I tend to draw my own maps - as it's something I enjoy doing: and the key to enjoying it, the key to producing maps that will challenge and reward the mapper - is to ensure that you, the author of the map, are likewise inspired. If you enjoy what you do while you're doing it, you're more likely to produce an inspired product: one which the player will enjoy unwrapping.

To start, grab an image, or an idea, or other visualization that strikes you. A bird might work - or a geographic pattern. Imagine what it would look like pixelated, and draw that out - these are your initial halls and rooms. From there, think of some shapes you haven't used yet - as you draw, see if there are some shapes you like that you want to repeat: draw them. Incorporate them. Don't be afraid to take up a lot of horizontal space - too much on a page can create clutter: and some white space can lend itself towards a more esthetic layout. Alternatively, you could draw a maze - if that's what you're vision says - in which case, the guidance still applies: recall, most parties are going to be between 8 and 12 bodies: not necessarily 8 to 12 players, but four to six players each with a hireling, henchman, and torch-bearer or two. If the goal is to create cramped conditions and a feeling of claustrophobia, a ten foot hallway twenty feet long, though seeming a big space on graph paper, is plenty small enough for an adventuring party to get cramped cramming into. On a battle grid or VTT, after all, 10 by 20 feet is the bare minimum to accommodate our aforementioned minimum party of eight tokens! So - you can make it cramped if you want: but recall, don't be afraid to make it sprawl. It is always more cramped in play than it feels on paper (or in pixels, if you're drawing it virtually).

Then, make some alternate ins, alternate outs, from various sections - looping, as some folks call it, or jaquaying - leaving some places as dead ends if it makes sense for them to be dead ends, but creating circuits elsewhere: provide re-usability for the map - make the players want to explore more than once to see the ins and outs, or give the players (or monsters!) a way to move around more quickly, or to out-maneuver a pursuing adversary (or adversary under pursuit!).

Lastly, figure out your secrets. Which dead ends - or which thoroughfares - should be hidden, based on what you envision being in there? How would a character in that area engage with the terrain in order to find it or to enter? Are there too few secrets? Consider blank spaces on the map - if other places don't have a blank there, consider adding a secret room: a good mapper will notice if a map feels uneven and the party will often times double back and give it another go in the event that the mapper says, "Something should be here."

For you, the author, a map is freedom. The map is the point where there really isn't a good substitute for experience: and it's an avenue for artistry for folks (like me) who can't really do real art. Have fun when you draw - and if you aren't having fun, use a generator for this step, instead. Anything to get your map and your dungeon closer to actually being played: at the end of the day, isn't that the point?

Stocking

Having identified your stocking tables, as sub-sections by faction or area or as a whole, next, label your rooms using the naming convention of your choice and start rolling! This is a fairly simple process - as such, existing resources (B and X come to mind as my go-tos) having a good grasp on the process, I won't wax poetic too much: but will instead focus on process.Rooms have three major elements:

- Treasure: the valuable elements that the player characters will want to take with them.

- Trim: the furnishings of the room - including traps, thematic elements, dynamic components to the room, or even mundane furnishings.

- Occupants: the monstrous (or not so monstrous) living entities in the room with whom the player characters can interact.

- In a separate "key" file - enter a line each for each room to stock, by room key. This list will allow you to iterate a specific series of action for each one.

- First pass, roll D6/6 determining room contents as a flag - so, does this room have treasure? True/False; does this room have a monster? True/False; and so on.

- Second pass, for each room with a monster, roll accordingly for occupants, based on the stocking table; note their treasure type, but do not roll it.

- Third pass, open the book to the unguarded treasure table. For each room that contains treasure but does not have a treasure type - note, to my personal taste, I will treat a monster with treasure type Nil as unguarded treasure for this purpose - roll unguarded treasure, as appropriate, for each. Note its net value.

- Fourth pass, open the book to the treasure type tables. For each room that has a treasure type, roll treasure accordingly. In this stage, it might stand to character to then do another round for magic items, gems, etc. - which you can, but I don't: gems and magic items are infrequent enough that I find flipping the page to them doesn't slow me down enough to warrant a dedicated pass. Note, again, the treasure's net value.

- Finally, sit back - look at your key, look at where the rooms are and their contents in relation to each other - and come up with short descriptions, evocative - preferably, to explain what's going on in those rooms - think of a one line reason why there is a trap here, or what are those skeletons guarding. In so doing, this will help to come up with elements for the ever-mercurial Special room result - but also it will produce a dynamic between elements, between monsters, within the dungeon - perhaps through randomization, producing a faction that you hadn't planned for.

This can help to reinforce your theme - to run with the canopic jars example, it would be a much better fit for those jars to appear when breaking into the embalmer's room in the tomb of an ancient mummy than it would be to find a stack of coins lying around. Similarly, it would be much more thematic to find a 100 gold piece torc when rummaging through a cairn to a pictish hero than it would be to find 100 gold pieces. Sometimes, you'll want to take liberties with the weights - assuming you run encumbrance rules - but all in all, it's not hard to make up the difference elsewhere: or, knowing that there will usually be more treasure in a larger floor than the party is going to haul out anyway, it's also not hard to not worry too much about it. Picking the right treasure to haul is part of player skill, managing inventory management and encumbrance.

This can help to reinforce your theme - to run with the canopic jars example, it would be a much better fit for those jars to appear when breaking into the embalmer's room in the tomb of an ancient mummy than it would be to find a stack of coins lying around. Similarly, it would be much more thematic to find a 100 gold piece torc when rummaging through a cairn to a pictish hero than it would be to find 100 gold pieces. Sometimes, you'll want to take liberties with the weights - assuming you run encumbrance rules - but all in all, it's not hard to make up the difference elsewhere: or, knowing that there will usually be more treasure in a larger floor than the party is going to haul out anyway, it's also not hard to not worry too much about it. Picking the right treasure to haul is part of player skill, managing inventory management and encumbrance.Treasure vs Hazard Audit

We've all heard - and many of us experienced - the problems associated with too-much treasure: the Monty Haul game, wherein player character wealth grows out of hand and compromises the game by its buying power in a medieval population that runs on a denomination of wealth an order of magnitude smaller than the amount of wealth extracted. We've also experienced, though, the overbearing response to the threat of wealthy players - that is, stingy GMs. To account for these potential outcomes, I tend to keep a treasure audit versus the hazards that I've generated.Each time I note the value of the treasure to be found in a room, I keep a running sum -

potentially just putting it, one line at a time, in an Excel column. For me, and I don't know if it's just that I roll cursed dice to generate treasure - but I'm far more likely to randomly generate a small treasure than a big one. For that reason, I try to add treasure - potentially in places it would make sense for it to be - to bring the audit up a bit. I don't have a number in mind when I do this, in terms of "how much treasure is this versus how much would a party of the same level as the dungeon or dungeon level being mapped is intended to be need to level" - but instead eyeball it: would I, knowing the hazards therein, risk myself against those hazards with the promise of the treasure at hand? If I wouldn't, then I add some more - knowing that the party likely isn't going to find or extract all of it, that may change the number.

potentially just putting it, one line at a time, in an Excel column. For me, and I don't know if it's just that I roll cursed dice to generate treasure - but I'm far more likely to randomly generate a small treasure than a big one. For that reason, I try to add treasure - potentially in places it would make sense for it to be - to bring the audit up a bit. I don't have a number in mind when I do this, in terms of "how much treasure is this versus how much would a party of the same level as the dungeon or dungeon level being mapped is intended to be need to level" - but instead eyeball it: would I, knowing the hazards therein, risk myself against those hazards with the promise of the treasure at hand? If I wouldn't, then I add some more - knowing that the party likely isn't going to find or extract all of it, that may change the number.Are the players going to know beforehand what the hazard level is or what the potential reward may be? Of course not. That's part of the fun of playing. However, I as the referee, I want them to feel rewarded. I want them to be able to weigh their options fairly - some maps will have more treasure, some maps will have less: and sometimes one will appear the other based on how the players interact with it during the session - what they find, what they encounter, how they roll, ... - so, when stocking for treasure, behind the scenes, I tend to try to maintain that balance.

Them's My Two Coppers

Now get out there and build, dungeon makers!Public domain art respectfully pilfered from OldBookIllustrations.com, ReusableArt.com, Wikimedia Commons, and the National Gallery of Art in June and August of 2020. Attribution in alt text.

No comments:

Post a Comment